The following article appeared in The Post-Journal on April 6, 2023, and was written by Eric Tichy.

Chris Gibson quickly looked through a handful of photographs that, moments earlier, had carefully been spread out on the table in front of her. She stopped at the one she was looking for — her son, Ben, in his Forestville high school football uniform.

“He was a talented football player,” Gibson said, holding the photo. “He played football from midgets all the way through high school and first year of college.”

She noted her son’s love for his two daughters and a late-developing interest in computers and amateur (ham) radios. As a child, he was involved in 4-H where he got to show off his horses.

Gibson isn’t sure when or how her son’s path toward substance use disorder began. She and her husband, Sean, both worked as substance abuse counselors.

“We tried repeatedly to help guide him toward a lifestyle of recovery,” Gibson said.

His death in January 2022 at the age of 31 due to addiction was and still remains a traumatic experience.

“When you have a loved one with substance use disorder, you’re always kind of on edge, you know, the reality that something like this could happen is there,” Gibson said. “But when it happens, it still catches you off guard.”

Heartbreak due to what has become an opioid crisis in the U.S. also has been felt by the family of 24-year-old Brandon Zebrowski, who died of an overdose in June 2020.

According to his sister and aunt, Brandon was very outgoing and had lots of friends. He worked for the U.S. Postal Service delivering mail in Jamestown and Frewsburg.

“He was navigating life in a healthy way and just trying to find his place,” his aunt, Michelle Williams, said. “And he was just taken too young before he had an opportunity to even really understand what he was doing.”

Williams believes her nephew’s addiction started slowly with drugs that happened to be available.

Maddie Surrena said her brother didn’t seem to fit the stereotype of someone struggling with addiction. Brandon went to work every day and was incredibly outgoing, hanging out with his friends and working out for fun, she said.

“It was unexpected because, you know, you kind of think of the negative stigma — people who are living on the streets,” she said. “You don’t really think of people who are fully functioning all day.”

TIME TO ‘RISE’

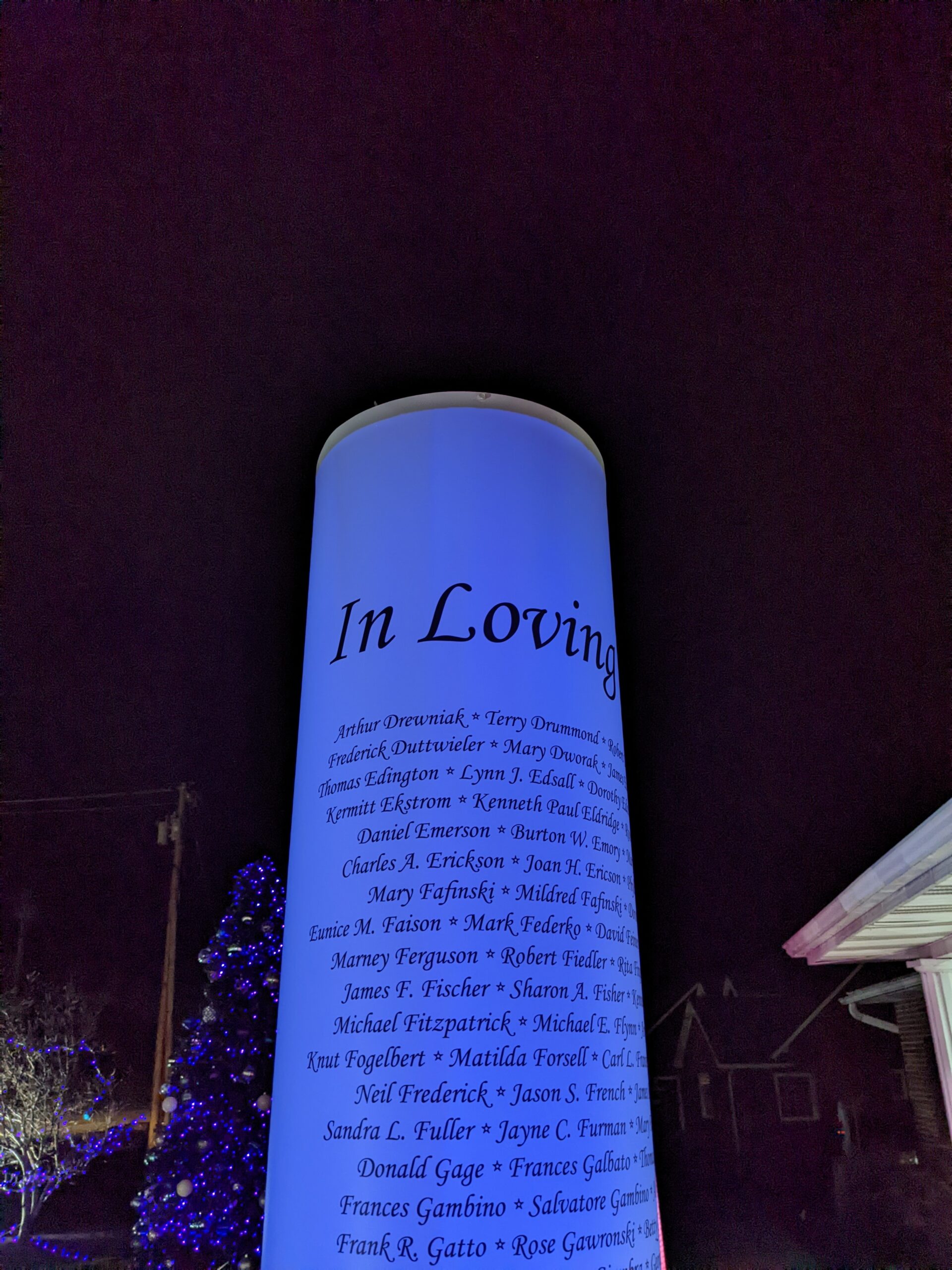

For the past several months, Chautauqua Hospice & Palliative Care has been developing a group for people who have experienced a death due to addictions.

Carna Smith, a grief counselor with the organization, said some grievers have found that they don’t “fit in” with other support groups. “People who have not struggled with a loved one in addiction often do not understand addiction loss and are, quite frankly, afraid of it,” she said.

Talks at Chautauqua Hospice & Palliative Care resulted in RISE — Recovery, Inspiration, Support and Education. The group’s mission, Smith said, is to “offer comfort, hope and support to anyone grieving the loss of a loved one from alcohol or drug-related causes.”

Members meet from 7 to 9 p.m. the fourth Thursday of every month at the Hospice office on Fairmount Avenue in Lakewood.

“I think what we’re trying to do that’s different is there’s lots of advocacy groups, there’s lots of groups and agencies that focus on prevention and getting people clean and getting them into a healthier life,” said Jamie Probst, director of bereavement. “But all of that, in a lot of ways, it’s taboo to talk about what we need to talk about.”

There is no cost to attend the sessions, and the group is planning to engage in community awareness and advocacy for addiction-related legislation at local, state and federal levels.

“We can’t look at addiction medicine any differently than any other medical diagnosis or complication,” Williams said, “And yet, society still does, and that stigma presents as barriers to the grieving process to support systems because it’s looked at as unique; we’re still placing the blame on the victim, because people don’t understand that as a brain disorder.”

‘FENTANYL POISONING’

Gibson and Williams are both quick to highlight the dangers of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine.

Ben and Brandon both had fentanyl in their systems when they died.

“We refer to it as ‘fentanyl poisoning’ because, the history of substance use aside, fentanyl can kill somebody on the first attempt,” Gibson said. “So there’s no more safe way for kids to experiment. One pill can kill, and although our son had a history of substance use disorder, the fentanyl is the determining factor. And that’s why we choose to call it fentanyl poisoning.”

Williams, a clinical social worker, alluded to the “old school” sobriety only, zero tolerance approach to treating addiction. She said treatment today can be aided with medication while helping users identify potential underlying emotional issues.

She referenced harm reduction, described by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration as “approach that emphasizes engaging directly with people who use drugs to prevent overdose and infectious disease transmission, improve the physical, mental, and social wellbeing of those served, and offer low-threshold options for accessing substance use disorder treatment and other health care services.” SAMHSA is a branch of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Williams said there needs to be a more open-minded approach to different recovery options.

According to the Associated Press, since 2020, drug overdoses are now linked to more than 100,000 deaths a year nationally, with about two-thirds of them fentanyl-related. That’s more than 10 times as many drug deaths as in 1988, at the height of the crack epidemic, the AP said.

Gibson said her son did carry Naloxone, medication that rapidly reverses an opioid overdose. But with fentanyl widely circulating in the community, many users may not be aware what they are taking.

“If you look at (past) overdose deaths … they didn’t die from heroin overdoses because they knew what they were doing,” she said. “But people are dying because fentanyl is in the mix now.”

Brandon’s family opted to be open about his struggles. His obituary notes his “courageous struggle with addiction.” It further reads: “The family has chosen to share this information in hopes that others will learn the importance and seriousness of addictive disorder. The message needs to be clear to stop the stigma as it affects us all.”

In addition to support groups offered by Chautauqua Hospice & Palliative Care, there are several countywide services and providers for individuals and families struggling with addiction. Details and contact information for those resources can be found at CombatAddictionCHQ.com

The Chautauqua County Crisis Hotline (1-800-724-0461) provides free confidential assistance, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week and is staffed by behavioral health professionals.